Joe and Elizabeth Seamans began their careers in public television. Joe specialized in producing and directing documentaries, including specials for National Geographic. Elizabeth devoted a large portion of her career to writing for Fred Rogers. Their recent filmmaking collaborations have a quiet, meditative style that caught the attention of Eddie Hauben, a friend of theirs and yogi with a long history with IMS who was looking to produce a film about the retreat center’s beginnings. Eddie asked if they would be interested in making the film and both agreed that it was a story that needed to be told. Despite many challenges, foremost amongst them filming during a pandemic, Inside Insight: The Founding Story came into being. Here, IMS Staff Writer Raquel Baetz talks with Joe and Elizabeth about the process of making the film, why they decided to be involved with this project, and their thoughts on the final product.

Tell us a bit about your professional backgrounds.

Joe: We both started working in public television in the early 70s. I was interested in photography in school, and ended up working at WQED, a public television station in Pittsburgh in the film department on a local news show and making documentaries. The station grew into a PBS flagship station, so I got a chance to film and eventually produce and direct National Geographic Specials when they were on public television, Nova programs for WGBH, and a lot of science programming. The filmmaking process, for me, was always about public television for the most part.

Elizabeth: I started out as a journalist and ended up working for Fred Rogers at “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood.” For about 30 years we worked closely together—from the time I was 23 until I was in my mid-50s. I was a script writer for the program, and, strangely, appeared as Mrs. McFeely, the postman’s wife. It’s an odd little part of my resume. I also did some filmmaking, making documentaries under the umbrella of Fred’s company. They were mostly documentaries to help train schoolteachers, police officers, and others about how to help children when there’s violence in their communities.

What is your background with meditation?

Elizabeth: The film’s producer, Eddie Haubin, who is really the hub of the wheel of all of this, was my meditation teacher in an informal sense. He’s very close to Joe’s sister and her husband, and that’s how I met him. We used to meditate together. I’ve had an off and on meditation practice since forever, belonging to different small sanghas in Pittsburgh. I’m an imperfect and inconsistent practitioner, but I have a long practice which has served me very well for many years.

Joe: I became aware of mindfulness and meditation in the late 60s. I took a photography class from Minor White who was very informed by Buddhist practice. We would practice meditation to help us look at what was in front of us with an open mind, without preconceptions. So, I do meditate. And, as many people are these days, I’m quite aware of the growth of mindfulness in our culture.

How did you get involved with making this film?

Elizabeth: We made a movie about a man who trains and logs with mules in the rural South. He’s a third-generation logger, deep in the country, and we went and spent time with him. It’s a quiet, meditative piece. The format is a lot like the one we ended up with for the IMS film. Eddie really liked that movie, and I think he realized that this was a moment at IMS, when a story needed to be told. And I think that the style that we work in really appealed to him.

Joe: He asked us if we would be interested in making the film and we thought about it carefully and decided, yes. IMS is an institution that Elizabeth is quite attached to, and I thought it would be kind of interesting to hear people’s stories. We went into it with an open mind and decided we’d keep it simple and just document the stories and the history. There was no expectation of what the film would look like at the beginning.

How did you decide the best way to present the IMS story?

Elizabeth: There was a notion of we’re going to go to IMS, and just be there with the camera. In the beginning we thought we would spend a few days during a retreat, and then came Covid, and there were no retreats. But in the end, we felt that we would still go. And we think it was a vast improvement over trying to film during retreat. Covid allowed us to be in that space and look at every detail of it in quiet. We now think it was a blessing.

Joe: It was also a bit of luck that during the few days we were at IMS there was a beautiful stretch of October weather, and the leaves were in full change of color, so there was a kind of luminance that permeated all the empty spaces. It looked beautiful.

So, we had an adventure up there for a few days. We had the run of IMS and could quickly move around and take advantage of the light, and not worry about getting in people’s way. So, it worked out very well.

Your approach to filmmaking sounds like what one’s approach to meditation practice might be.

Joe: Yes, I agree. For one thing, trying not to have any predetermined outcomes. You need to have some kind of basic framework. But when things don’t work, for example, with Covid, you have to try to embrace that.

Elizabeth: Working with Fred Rogers, who used a lot of silence and spaciousness in his work, I think the idea of looking and listening and being present is core to me in the work that I do. And I do think that there are things in the practice that are embedded in how we made this film.

Could you talk a little more about your process. How do you go about making a film and how do you decide what to put in and what to leave out?

Joe: So, there’s a narrative that begins to build out of all these personal stories. For example, this unexplainable desire on the part of the founders to take a course at school and then head to Asia—independently—which was a big deal in those days. That story drove everything forward. This was what the movie was about—how things kind of stumbled and rolled forward in time, and led to the buying of the building, and so on.

We shot a lot of interviews, and then they were all transcribed. We’re big believers in getting it all down on paper—and electronically—so that it can be edited that way. Then Eddie spent a lot of time going through to mark what we should use because he knows so much more about the subject than we do. Then I took those transcripts and selected comments from each person and put it into thematic buckets which included comments from others on the same topic or specific part of the story. Those buckets eventually became the chapters in the movie. Then once all the comments were in the buckets, I tried to organize each one to tell the story as clearly and dramatically as possible. I also eliminated a lot of repetition. And then I used the edited comments in each bucket to make the video.

At that point we had about a two-and-a-half-hour video. Then the big question: how to eliminate commentary and how much to eliminate? Some of the time, overlapping comments are great because people say things slightly differently. It’s taking advantage of everybody telling their own story. But sometimes you can leave the audience hanging with one person’s thought, and then pick it up with another person’s. I learned it’s even okay to leave gaps in the narrative. People can fill them in for themselves.

So, we said, let’s try to cut it in half. That was my next job. And it seemed to flow better as a shorter thing.

Aside from Covid, what were some of the other challenges?

Joe: It’s much easierwhen someone comes to us, and says, this is the film I want.

Elizabeth: But then we would never have made it.

Joe: The fact that nobody had any real expectations made it quite challenging, because you’re left with your own expectations, trying to figure out, “What is this movie and how does it work?” That was a big challenge for me. But it was wonderful, too, because it was challenging.

Everyone let us do what we needed to. It’s quite a simple movie, but there’s a lot that goes into leaving it like that. Keeping it simple is challenging.

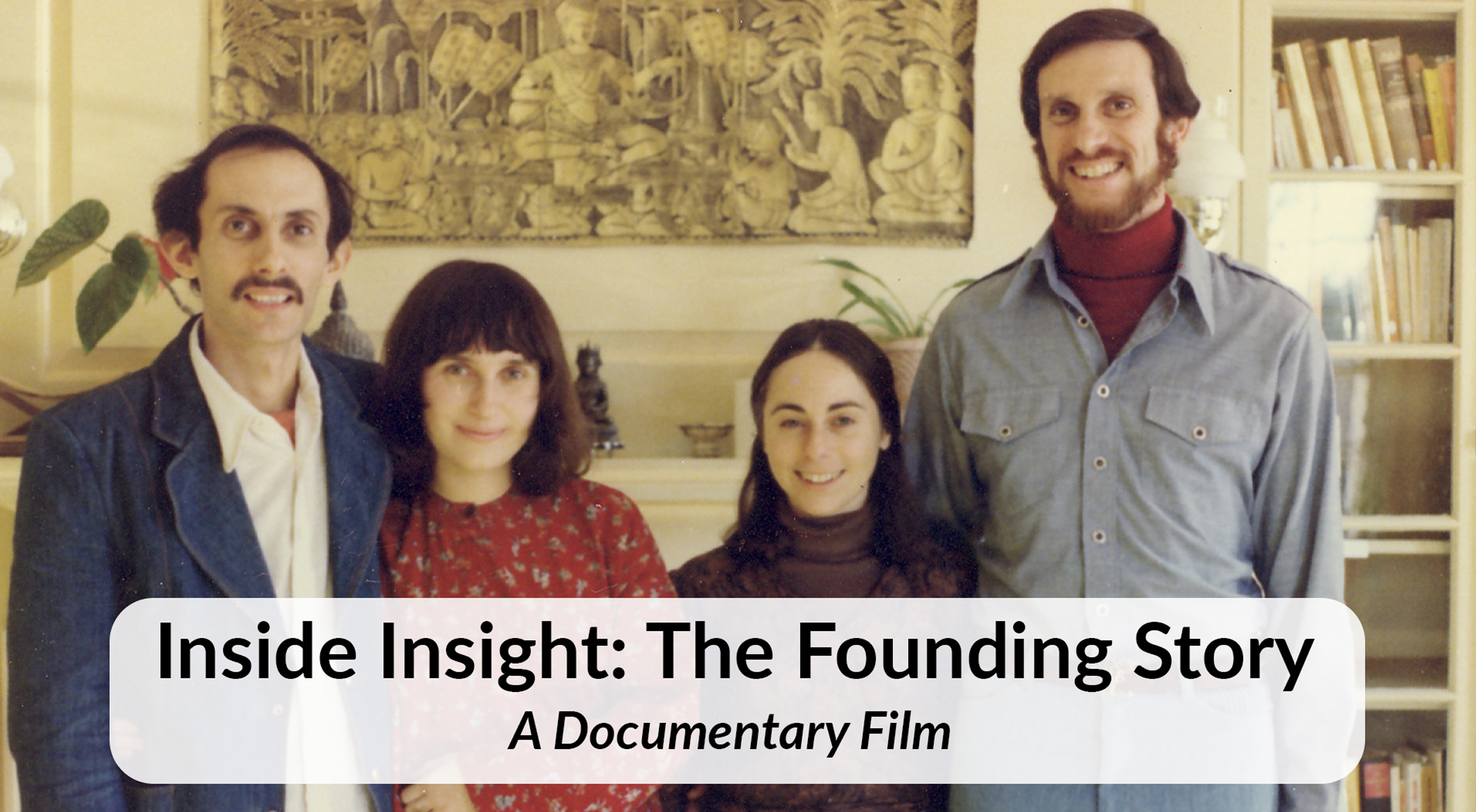

Once the narrative is built, then you can plug in photos—Steven Schwartz, for example, in his prom tuxedo, or the wonderful image of Sharon Salzberg standing in front of the pachinko machines, or Joseph Goldstein on his way to the Peace Corps wearing a jacket and tie—they’re very touching pictures.

Elizabeth: When you’re working with interviews—some stories are better told than others. Once Joe and Eddie got down into the weeds of choosing pieces out of the hours and hours of interview, there was a crucial balance between Eddie’s knowledge of Buddhism and IMS and Joe’s artistry. There was lots of stuff that Eddie loved, but from a dramatic point of view, it couldn’t be folded into the structure. And Joe could see from an artistic or storytelling point of view what needed to be in the film to move it along. Eddie and Joe have a good relationship which allowed them to trust each other with the material.

You mentioned that if you had been told how to do the film, you wouldn’t have gotten involved. Can you say a bit more about that?

Elizabeth: This was not at all a commercial undertaking. It was an affair of the heart. If IMS had come to us and said, we want you to do a history of IMS, and we want all this archival footage and we want it to come out like this, I might have said, that sounds like a great magazine article or even a book, but it’s not a video we want to make.

A video is the next best thing to being there. And that’s how I like to use it. For example, with our work in the rural South, most people could not get into that closed community where we happen to have family ties. But being able to abide in the space—with our cameras—that’s special.

I’m just lucky that I’m old enough and secure enough that I can only do projects that I really love. And I loved—and we loved—this project, and we learned a lot from it.

Joe: Eddie did a great job of interviewing everybody. He made them feel comfortable and so they were open about their experiences and observations. The interviews were very conversational. In one example, Sharon and Jacqueline Mandell tell the story about staying in Joseph’s apartment in Boulder, Colorado. And Joseph reflects on how imposed upon he felt until he realized he was under the illusion that it was his apartment. It isn’t just what people said, but also how they said it that makes these personal reflections special. It’s easy to lose that quality with all the lights and camera present, but Eddie cut through all that with everyone and it shows.

This reminds me how relatable and funny some of the stories in the film are and how it makes the practice and IMS accessible to a wider audience.

Joe: You’re right. It was a gut feeling I had to include, for example, Steven Schwartz talking about the hot water tanks—they’re like a character in the film. In fact, I noticed in a comment about the movie, someone asked, “What happened to the oil tanks?”

Elizabeth: And it’s a part of being present with people—the humor. You really want to give people the sense that they’ve had an experience of being at IMS and not just information. One of the things about making these kinds of films that is so crucial is not to get too fact-based or too driven by a narrative, but that one of our underlying goals or intentions is just to abide in this place, to be here with these people fully.

Joe: It all starts with a good subject. Why is it a film? Why do people want to look at it? Because the story is very compelling, and the people who are telling it are very compelling. That’s it in a nutshell: is there’s something there? If there is a great story to tell, you try to give it life, and let it go.

I think for me, also, not being privy to the story ahead of time was a big help too, because a lot of these stories are what we would call “family stories” or stories that come up again and again.

Elizabeth: It’s the family folklore of IMS.

Joe: Yeah, but hearing it for the first time, you go, “Wow! That’s amazing.” And there may have been times when I said to Eddie, “This is really great.” And he would question, “Really?” Because he’s inside a little bit so he may have heard the story before.

Final thoughts on the film or the process?

Elizabeth: I love making films, and I love showing them to the people who care most about them. And talking to Joseph after the premier in Barre, I said to Joe, “Joseph loves the movie—that’s the Academy Award.” If people who I respect and are knowledgeable about the subject feel that it’s good, I’m totally satisfied.

Joe: I think that’s true of me, too. If the people who are in it like it and feel that it’s a fair representation of what they had to say, that’s very gratifying. And Joseph reflected that at the screening, so I also shared Elizabeth’s joy in that.

I think there is value in the film because it shows how people followed a path one step at a time, and that led to something that has a considerable degree of permanence. Here we are after 50 years! IMS is off to a good start!

Elizabeth: It was a privilege to work with the people in the film and to get to know more about IMS. We’re so happy that the film is out there. I think that we made the movie for you all. It was a gift.

Joe: And a gift to us. It was an honor to work on this project, and I think it’s something that’s of great value: to have a story of how IMS came to be.